Anthropology and Historiography

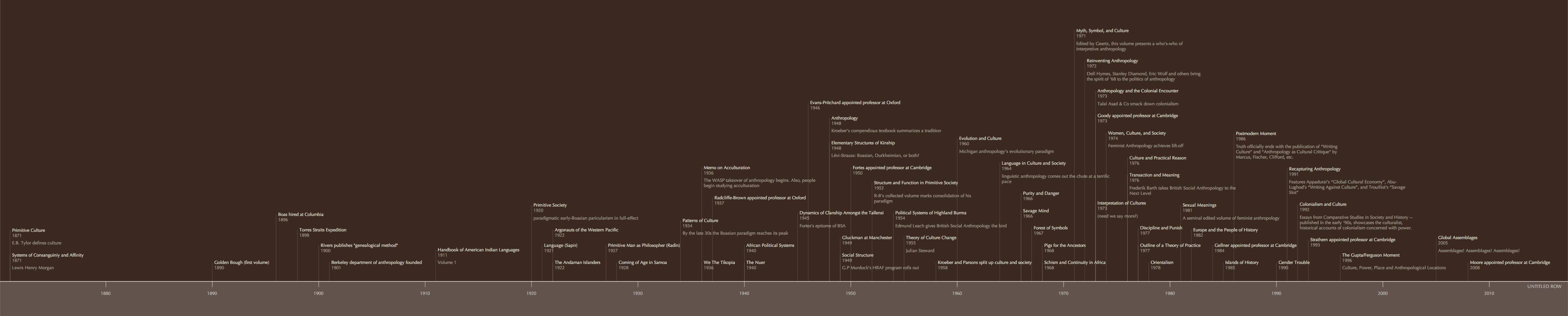

This essay demonstrates how historiographical work has changed over time, alongside the development and emergence of anthropology. In order to understand how anthropology has influenced the methodological practice and perspective of contemporary historians, we first need to understand anthropology as its own discipline.

In its broadest definition, anthropology is the study of human societies and cultures. Anthropologists study human development through the analysis of biological evolution, environmental factors, communicative practices, social interaction, and material culture. Prior to World War I, the terms anthropology and sociology were used interchangeably. However, sociologists focused on the study of social relations and their influence on societal development and progression; whereas, anthropologists studied a larger scope of society. Historians, more so, distinguished truth in the origin, development, and functionality of human society. In other words, sociologists studied how?, anthropologists studied what?, and historians studied why?, but, collectively, all focused on human history.

Roots of anthropological and sociological studies are found in Greek antiquity. Early historians Herodotus and Thucydides sought to preserve the truth of the human past through a method of inquiry and analysis of evidence. This practice stood out as different from earlier intellectuals in “their attempt to define history as a distinct method of telling the story of the past” (Popkin, 2016, 27). For this reason, we can consider Herodotus’ Histories and Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, as the start of historiography in the Western world.

However, the collapse of Rome and the political establishment of Christianity in the fifth century shifted the historiography of human history. After which, historical works focused on divine origin and “the purpose of the historian [was] to show the working out of God’s plan for humanity” (Popkin,2016, 37). The Catholic Church positioned itself as the authority over historical scholarship and therefore, “medieval historians often began their works with a summary of world history, drawn from the Bible and Roman sources” (Popkin, 2016, 40).

Yet, at the same time in Asia, historians utilized scientific theories to understand society. In China “rulers of the Tang dynasty created an official History Bureau, charged with recording the events of the region” and Chinese historian Sima Guang “argued for the importance of evidence from archaeology as a way of verifying claims made in written sources” (Popkin, 2016, 42). In the Arab world Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddima “develop[ed] one of the first non-religious social theories, and anticipated Emile Durkheim’s ideas (discussed below) about social solidarity, which are today considered a cornerstone of sociology and anthropology” (Ericksen and Nielsen, 2001, 5).

It was not until the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries that historians adopted secularized views of social history in union with scientific critique. An era defined as a “society [which] had emerged as an object to be continuously ‘improved’ and reshaped into more ‘advanced’ forms [in which] the independent, rational individual [can] change into someone new and different, and even truer to its nature” (Eriksen and Nielson, 2001, 11). Inspired works, such as Giambattista Vico’s La Scienza Nuova, Immanual Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, became some of the most influential histories to mediate concepts of individualism, class, property, and progression of human civilization.

Social changes during the 19th century caused the divergence of anthropology and sociology into two distinct sciences (Green and Troup, 1999, 172). The French philosopher Auguste Comte first coined the term ‘sociologie’, but economists like Karl Marx and Max Weber expanded on Comte’s social theories as capitalism and political modernity engrossed Europe (Green and Troup, 1999, 110). Additionally, Emile Durkheim’s Les Règles de la Méthode Sociologique legitimized sociology as a science and laid the foundation for Functionalism, a theory stating “that all aspects of society were interrelated and therefore society should be studied as a whole” (Green and Troup, 1999, 174). So, “while historians charted the rise of nations, anthropologists traced the cultural and social evolutions of mankind” (Green and Troup, 1999, 172). Thus, as biologists Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer formulated evolutionary theories of human history, sociologists Lewis Henry Morgan and Edward Burnett Tylor developed the concept of culture. As defined by Tylor, “[culture] includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society” (Green and Troup, 1999, 172).

In 1929 Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre established the foundation for the Annales School. This new institution promoted ‘La Longue Durée’, long term histories and total-histories which implemented anthropology, geography, history, and sociological theories. The practice of anthropology as a science in union with humanities transcended historic anthropology from a social phenomenon to a cultural one. Anthropology therefore, “redirected historians attention away from the public, political sphere of human action towards private, daily life, by rediscovering old sources, including oral history and tradition” (Houses, p. 174). These new methodological practices focused on quantitative analysis by way of fieldwork, participant observation, and examination of material culture.

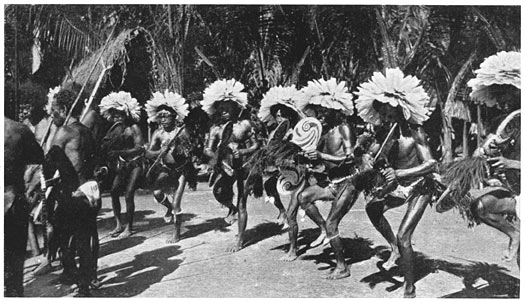

German anthropologist, Franz Boas, “Father of American Cultural Anthropology”, expanded the development of culture based on his observations of indigenous Native American cultures. In his publications The Mind of Primitive Man, Boas applied ethnographic analysis to his framework, stating, “each people, each nation, each tribe had its fate, its irreplaceable character, and it was the task of the anthropologist to document and defend it” (Eriksen and Nielsen, 2001, 49). Not until the end of World War II was an equilibrium between social and cultural analysis formulated into Functionalism.

Some of the most influential works in historiography came in the 20th century, as Bronisław Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific influenced anthropological methods of participant observation and fieldwork. These were key approaches to understanding history as it gave “all around vision” of man and culture. Alfred Radcliffe-Brown’s and E.E. Evans-Pritchard’s methods in social anthropology gave new insight to behavior as “social institutions and relationships were perceived as mechanisms which ensured the survival and stability of the social system as a whole” (Green and Troup, 1999, 173). Moreover, Intrepretive Archaeology and Narrative was developed and implemented into Clifford Geertz’s The Interpretation of Cultures. Geertz’s approach to history used ‘thick descriptions’ to “get beneath surface behavior to reach an emic (insiders’) understanding” (Green and Troup, 1999, 177). Geertz deduced

“the conjoining of History and Anthropology is not a matter of fusing two academic fields into a new Something-or-Other, but of redefining them in terms of one another by managing their relations within the bounds of a particular study: textual tactics. That sorting things into what moves and what moves it, what victimizes and what is victimized, or what happened and what we can say about what happened” (Geertz, History and Anthropology, 329).

By the middle of the 20th century the culmination of both disciplines, history and anthropology, consolidated.

Thus, Ethnohistory emerged as, “the study of the history of the peoples normally studied by anthropologist[s]” (Green and Troup, 1999, 175). W. C. Sturtevant explained “ethnohistorians add another criterion for estimating reliability and bias” (Sturtevant, 2002, 13). Further, historian James Axtell states, “ethnohistory encompasses archaeology, ethnology, history and linguistics, and the source materials available to the ethnohistorian which include folklore, oral tradition, maps, paintings, and artefacts, as well as written sources” (Green and Troup, 1999, 175). As Postmodernism emerged in the late 20th century historians were able to access new technologies, resources, and accepted multiple perspectives on history. This included histories previously ignored, such as gendered and indigenous perspectives, which have been dominated by a male, Eurocentric narrative.

Nevertheless, we do not know how anthropology will influence historians of the future. Natalie Zemon Davis, Canadian and American historian of the early modern period, states that historians can still learn from anthropology through “close observation of living process[es] of social interaction; interesting ways of interpreting symbolic behaviour; suggestions about how the parts of a social system fit together; and material from cultures very different from those which historians are used to studying” (Green and Troup, 1999, 177).

Though historians will never completely know everything that has occurred in history, anthropology has given historians the tools to better understand the past. Allowing for the prediction to be made that anthropology will continue to contribute to historiography as new topics are explored and vice versa.

References

Axtell, James. 1979. “Ethnohistory: An Historian’s Viewpoint.” Ethnohistory 26 (1): 1. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=hlh&AN=7680830&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Bruce G. Trigger, author. 1982. “Ethnohistory: Problems and Prospects.” Ethnohistory, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/481006.

Dube, Saurabh. 2007. Historical Anthropology. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2007.

“Emile Durkheim: Selected Writings.” n.d. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://web.b.ebscohost.com.libproxy.unm.edu/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzcxMTY3NV9fQU41?sid=e53a86d2-de1a-4d70-8080-0307b2132b75@sessionmgr120&vid=7&format=EB&rid=1.

Eriksen, Thomas Hylland, and Finn Sivert Nielsen. 2013. History of Anthropology. Anthropology, Culture and Society. London : Pluto Press, 2013. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06111a&AN=unm.EBC3386723&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Franz Boas, author. 1904. “The History of Anthropology.” Science, no. 512: 513.

“From Herodotus to H-Net: The Story of Historiography.” n.d. Accessed May 7, 2018. https://platform.virdocs.com/app/v5/doc/223267/pg/38/search.

Geertz, Clifford. 1990. “History and Anthropology.” New Literary History, no. 2: 321.

Green, Anna, and Kathleen Troup. 1999. The Houses of History : A Critical Reader in Twentieth-Century History and Theory. New York : New York University Press, 1999.

Harris, Marvin. 1991. Cultural Anthropology. New York, NY : HarperCollins, ©1991.

Jacobs, Brian, and Patrick Kain. 2003. Essays on Kant’s Anthropology. New York, UNITED STATES: Cambridge University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unm/detail.action?docID=217815.

Libera, Zbigniew. 2011. “History and Culture: Problems of Cultural Anthropology and Historical Anthropology.” Anthropos 106 (2): 597–602. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23031633.

Michael E. Harkin. 2010. “Ethnohistory’s Ethnohistory: Creating a Discipline from the Ground Up.” Social Science History, no. 2: 113. https://doi.org/10.1215/01455532-2009-022.

“Political Anthropology : Power And Paradigms.” n.d. Accessed April 24, 2018. http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzIwMDY5NV9fQU41?nobk=y&sid=0ad9527b-6b01-44dc-9e75-fea8ef3bfbd1@sessionmgr103&vid=4&format=EK&lpid=p01&rid=0.

Radcliffe-Brown, A. R., and Adam Kuper. 1977. The Social Anthropology of Radcliffe-Brown. London ; Boston : Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05987a&AN=unm.3364444&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Scutt, Cecily, and Julia Hobson. 2013. “The Stories We Need: Anthropology, Philosophy, Narrative and Higher Education Research.” Higher Education Research & Development 32 (1): 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.751088.

Smith, M. G. 1962. “History and Social Anthropology.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 92 (1): 73–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2844322.

Strenski, Ivan. 2014. Malinowski and the Work of Myth. Princeton, UNITED STATES: Princeton University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unm/detail.action?docID=1700296.

Sturtevant, W C. 1966. “Anthropology, History, and Ethnohistory.” Ethnohistory 13 (1/2): 1–51. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ant&AN=XRAI1957-79-25479&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Susan Kellogg, author. 1991. “Histories for Anthropology: Ten Years of Historical Research and Writing by Anthropologists, 1980-1990.” Social Science History, no. 4: 417. https://doi.org/10.2307/1171462.

Thomas, Keith. 1963. “History and Anthropology.” Past & Present, no. 24 (April): 3–24.

Tylor, Edward Burnett. 1883. Primitive Culture :Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom /. 3d American, From the 2d English ed. New York : http://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hn

1882 words.