Histories for Everyone

The Varied and Deep Tradition of Universal History

The ways in which people remember the past, has a certain effect on the future. If we could have one combined narrative that ties us all together as mankind, it would be called a Universal history. Universal histories, at their most fundamental level, detail histories which attempt to transcend particulars to form a narrative which applies to all the world’s peoples. As our documented and accepted histories today would tell us, this task of a universal history has been tried and failed. Universal Histories often fail in their goals, fall flat on further analysis, or are significantly limited in scope. They make assumptions or generalizations, based on perceived trends, religious expectations, or philosophical musings, that make it difficult to decipher the “truth”. Thus, in modern scholarship, we see an abandonment of these ancient traditions and narratives for more limited, small scale, historical analysis.

Ancient Narratives

Universal history as a discrete field is a relatively modern concept, yet the “idea” of universality can be traced further back. In mythic poetry we can see human themes which transcend the particulars, such as the struggle to return home, which is why Homer’s Odyssey is still pertinent today.Furthermore, philosophers central to Grecian thought, used history as a rhetorical tool, source of discussion, and spoke of universal themes. Despite the limits of Grecian perspectives, we can see universal elements to their writings. Meanwhile, Rome, as both the subject of Greek writers from its own historians, exemplifies the trend of transmitting a universal message.

Grecian Government

Grecian authors tended to assign universal causes to governmental trends. Authors such as Polybius and Strabo are often credited with using universal discussions in their work, dealing with the rise and fall of the Roman Empire. Their explanation transcends the specific and explains using the general.

Polybius and Strabo had an outsider’s perspective on the city of Rome, being Greeks to move to the rising republic.[rephrase this sentence, I’m not sure what you’re trying to say] Polybius in particular sought not only to explain this rise but also place it within the larger trend of civilization (Kelley, 31). Through his analysis, the rise and fall of Rome was one of the first of many such histories which sought to use Rome as evidence for larger historical trends. To Polybius, Rome rose due to its fear of the gods, and emphasis on a mixed constitution (Kelley, 34). The decay of Monarchy, Aristocracy, and Democracy was inevitable individually, but Rome, by mixing them, could buck this trend (Kelly, 34). Rome was not unique simply due to being “Roman”, but due to having these exemplary qualities of piety and diffuse governence in their civilization.

Strabo, in comparison, also deals with Rome’s government but encapsulates a more “discipline driven” viewpoint. Strabo shows how Rome viewed it’s destiny as arising out of universal causes, and applying universally. Fundementally, Rome’s rise to power was a benefit of it having a well managed government (Morcillo, 88). Strabo particularly viewed unified governments-as opposed to disparate, unguided ones-as being superior, due to their capacity to plan (Morcillo, 90). Because of this, the planned, superior Roman government, which progressively spread and encompassed the Mediterranean, was a universal destiny for the world (Morcillo, 95).

The Roman Destiny

The Romans themselves had a similar view of their successes. Romans were very aware of their larger place in the world, and strived to explain their position in it (Cornell, 111). Virgil, the great Roman poet himself stated that the Romans “keep universal rule over nations in these ways; by maintain peace by means of law, by doing justice to the lowly, by bringing down the haughty” (Mierow). Caesar himself couched his conquests in the “Imperial Mission” of Rome, for instance, showing the rhetorical influence and power of this ideal (Kelley, 53). The Roman Empire, as such, formed a history which could be imposed, a view of humanity in general which allowed Rome in particular dominance.

However this very rise to Empire would later prove to be Rome’s own undoing. Historians such as Tacitus viewed the imperial administration as hopelessly corrupt (Kelley, 63). In his reasoning, Tacitus framed societies as cyclical: progressing from innocence, into despotism, later corrected by law, which would eventually over correct and proliferate itself into another form of despotism (Kelley, 63). This progression of empires, mirroring Polybius’ take on Rome’s rise, did not seek to explain its misfortunes as merely being events, but rather inevitable trends in human history.

Theocracy and History

Yet as Rome fell completely its institutions and values would be destroyed, to be replaced by the Catholic Church, which waxed as Rome waned. Christian theological history contained that essence of transfer and empire that Rome managed to encompass, allowing its story to be sent to other places and peoples. However it was not shackled to a place or a people, transcending those particulars for a truly universal message.

In the earliest and formative period of Christianity, the major authors tended to be hermetic monks later deemed “Church Fathers” for their theological contribution. They, both collectively and specifically Augustine of Hippo, formed a universal paradigm which was followed by all medieval authors as the highest ideal of history. Augustine’s paradigm related how the new history was unique because it grasped the truth of God, thus differentiating it from earlier histories (Kelley, 90). In this manner historiography, and history itself as well, was framed as the progression from Pagan mistakes to Christian Truth (Kelley, 91). Orosius, a student of Augustine, further linked past events such as the pillaging of Babylon to the horrors of his time, and provided a master-narrative for the rise of Rome itself; Rome rose in order to provide the framework for the conversion of Europe to Christianity and the establishment of the will of God in law (Kelley, 94).

As Christianity became hyper-dominant, it substituted “Theology” and “Philosophy” for “History” as a mechanism for explanation and the discovery of causes (Kelley, 100). As such Histories were generally regulated to merely chronicling and explaining particular events, and placing them inside the larger paradigm of Christian history. Often, this manifested, as in the case of Bede, in parallel genealogical accounts showing Christain chronology, from the flood, to the “modern” era of Barbarian kings (Kelley, 110). This narrative-which encompassed what was perceived as all humanity-was thus truly universal, but divorced from particular historical analysis, and thus all histories began to utilize universal Christian themes, but did not truly innovate beyond them (Kelley, 124-125).

By the early medieval period the origins of nation states, and thus their unique histories and interpretations, were written as a coherent field in this tradition. Authors such as Jordanes, telling the Gothic story, Gregory of Tours for the Franks, and Bede for the English, all related more local perspectives that detailed pre-Christian tribes and the newer nations they became (Kelley, 106). However all of these histories were fundamentally Christian. The endeavor wasn’t so much to create a history of the Barbarians, but to link the history of the Barbarians to the universal history of Christianity; Jordanes account culminates in conversion (Kelley, 107), and Gregory exemplified Christian rulers and equates conversion and success (Kelley, 109). History differentiated, but only as a way of showing how Christian chronology, interpreted literally from the flood, related to the chronology and genealogy of their local subjects. These endeavors both told a universal chronical of mankind, and told a universal story that explained that chronical. Further analysis was relegated to detailing local events and religious events as pertinent to that narrative. Attempts to even relate divergent narratives, such as seen with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s writings on Merlin and Arthur, resulted in scorn for Barbarism (Kelley, 113 and 123).

The Rise of Secularism

It would not truly be until the Renaissance in the fourteenth-century that historical authorship becomes more secular, often revering Pagan authors and dealing more with the now rapidly crystalizing nation states of Europe. By the Reformation in the sixteenth-century, this secular perspective had come to largely dominate the historical field, and particular histories became more popular. With the growing Enlightenment, new, varied, and deep philosophical musings would come to dominate the field, encapsulating a new and blatant obsession with the universal. This would eventually be snuffed-out by more modern scientific scholarship. [expand a little more, or you could perhaps just mention the larger points of secularism here, and then in the following sections tell the story of how those themes came into being]

The Death of the Catholic Paradigm

The Renaissance is notable for how history had, in some ways, changed purpose. Authors such as Machiavelli wished to use it to compel political action, not merely relate how a people fit into the Christian narrative (Kelley, 146). Humanism began to relate non-religious narratives. As such, history began to focus more on the particular people and places of study; universalism in this period is most notable for its absence. Stories about city states (Kelley, 138), France (Kelley, 142), and Spain (Kelley, 156) were largely ignoring any attempts at universal narrative. This is not to say that Christianity vanished; in some places, such as Spain, authors utilized a universal Christian message or conversion to justify Spanish imperial ambitions and to explain the unknown (Kelley, 158).

This would become more obvious during the Reformation, which contained significant literary and religious modifications. On the one hand, humanism and secularism became more powerful as ideologies, and economics and technology favored the creation of more literary works. The trends that began in the Renaissance became more influential and powerful. Authors such as Bebel, who began to extort the glories of Germany and Le Caron who encouraged the development of a French identity as independent form antiquity, represented a departure from previous tradition (Kelley, 162). They focused on neither Roman common heritage nor Christianity to give common purpose, but began to relate the national traditions of local states (Kelley, 162). In this way, they emphasized particular causes over universal ones, and the overarching narrative of Christianity much more weakly than previous authors.

As an exception to this trend, there was also an outpouring of new religious histories. The new Protestant churches needed to interpret their place in the past, and to do so they had to create a new History. Authors such as Flacius Illyricus wrote on the transition of empires and held that the Reformation was merely a reconnection with the origins of Christianity (Kelley, 171). Others, such as Jean Crespin, emphasized how Martyrdom united all peoples, giving them something to aspire too (Kelley, 172).

However these writings, even as they engaged with the universal Christian narratives, became more segregated from the larger body of literature. That is not to say that there was a sudden lack of Christian influenced narratives of any denominations, and indeed Bishop Boussuet in the late 1600’s revisited and revised the narrative begun by Augustine of the fall from grace of man, emphasizing the divine providence of Rome and similar themes (Kelley, 212-213). However the long history of universalism being limited to Theologian Historians was truly fading, a byproduct of the expansion of humanism and, most importantly, rationalism into the larger field of history.

The Return of the Universal, and the Philosopher Historians

However as the Enlightenment begins, we see a resurgence of the analysis of empires. Vico utilized Roman authors in his analysis of historical trends, working with Tacitus and other authors (Kelley, 214). Vico attempted to blend Roman focused and divine focused narratives, mixing “profane” and “sacred” history, giving primacy to Christianity but still addressing other cultures and religions (Kelley, 214). In these authors we see attempts to explain specific historical events in universal themes-answering the why of the rise and fall of Rome, thus making that event indicative of the Rise and Fall of Empires. This, of course, is very similar to the way Polybius utilized Rome’s narrative, and these traditions did not exist in an ex nihlo vacuum; they arise, consciously, from those earlier writings.

Unique to these new universal histories, when viewed as a whole, was their scientific and rational perspective. The new ideal of rationalism, building on the humanist ideal of progress, conceived of man as inevitably becoming more rational and more moral. God may factor into this discussion, and often did, but his favor was no longer some ineffable power that could be used as the default explanation for events; God was part of the story, not the whole story.

This is exemplified by authors such as Leibniz, a major German author who utilized an “organic” metaphor for his understanding of human history. Leibniz is not unique as historian and philosopher, and is also a wildly recognized mathematician who is notable for independently developing calculus from Newton; he is representative of how varied the interests of these intellectuals were. It is important to note that Leibniz, and those like him, still utilized God in their writings; they merely utilized secular thought, rather than theology, as an explanatory mechanism. Leibniz viewed history as analogous to one animal body; Chronology represents bones, genealogy nerves, motives are like spirits, and the detail to the mass of flesh (Kelley, 213). Thus, history can be viewed, when freed of accidents and particulars, as a continuous and related body, with internal logic and connection (Kelley, 213).

This last sequence is where the emerging science of history becomes important. By making history more secular and encouraging discussion and speculation, they created a competition of ideas which, in turn, created a struggle for Truth. This scientific approach to universal history, and the attempt to purge history of falseness, is in contrast to ancient authors for whom history cared more for rhetoric. This transformation not only drastically changed the field of universal history, but ultimately killed it. [perhaps discuss the republic of letters in this section, Kelly 219)

The future of universal history

Universal histories, by their nature, require speculation and assumptions. It is inherently difficult, however, not impossible, to come to one “correct” master narrative, at least in the sense of universal history as a history of causes as opposed to events. Universal chronologies exist, but are trivium. Those universal historians that do exist tend to be controversial or ignored; Karl Marx is viewed as a “universal” historian due to his master-narrative of revolutionary cycles, but there is significant controversy over all his work (Christain, 5). Instead, focus is given to small scale “microhistories”, which detail specific events-similar, in some ways, to renaissance chronicles.

The modern historian David Christian, however, perceives a master trend where universal histories are temporarily sidelined by this emphasis on science (Christian, 5), only to return due to the abundance of perspectives and data now available (Christian, 8). Modern scholarship will, through collaboration with sciences such as anthropology and biology, develop both better chronological tools (Christian, 9) and utilize those perspectives to create a more complete historical picture (Christian, 10).

In particular, the new emphasis on minorities and women (who, while not a minority, have been ignored), and transcending the “colonialist” perspective of the past, both supports and contradicts this movement. On the one hand these are very particular perspectives, yet on the other they encompass the same goal to create a “history of everyone”, in a way that massively improves on the past. Even the most universal histories were really histories of male Europeans. Additionally, writers of such histories already face issues with “speculation” due to the lack of historical documents; it is a shorter leap today, considering the rise of these postmodernist influenced histories, to universality.

While these schools-of-thought are not necessarily truly predictive, they still offer a valuable perspective. Why shouldn’t they be true? Why should we not attempt to write a universal history of humanity, in the tradition of centuries of scholarship? I urge, as a final aside, that the reader not be intimidated by the fear of being wrong; universal histories have always had their place in historical scholarship, and regardless of validity, contain their own value and purpose. Lastly, I leave you the reader with a provocative question/thought, is it possible with todays technologies combined, with an international team of scholars could reach an accepted Universal History?

Works Cited

Kelley, Donald R. Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Marto Garcia Morcillo. The Glory of Italy and Rome’s Universal DEstiny in Strabo’s Geographika In Liddel, Peter P., and A. T. Fear, eds. Historiae Mundi: Studies in Universal History. London: Duckworth, 2010. Print.

Tim Cornell. Univerasl History and the Early Roman Historians. In Liddel, Peter P., and A. T. Fear, eds. Historiae Mundi: Studies in Universal History. London: Duckworth, 2010. Print.

[Christain, David. “The Return of Universal History”. PDF. Sydney: Macquarie University, December 8, 2010.] (thegreatstory.org/universal-history.pdf).

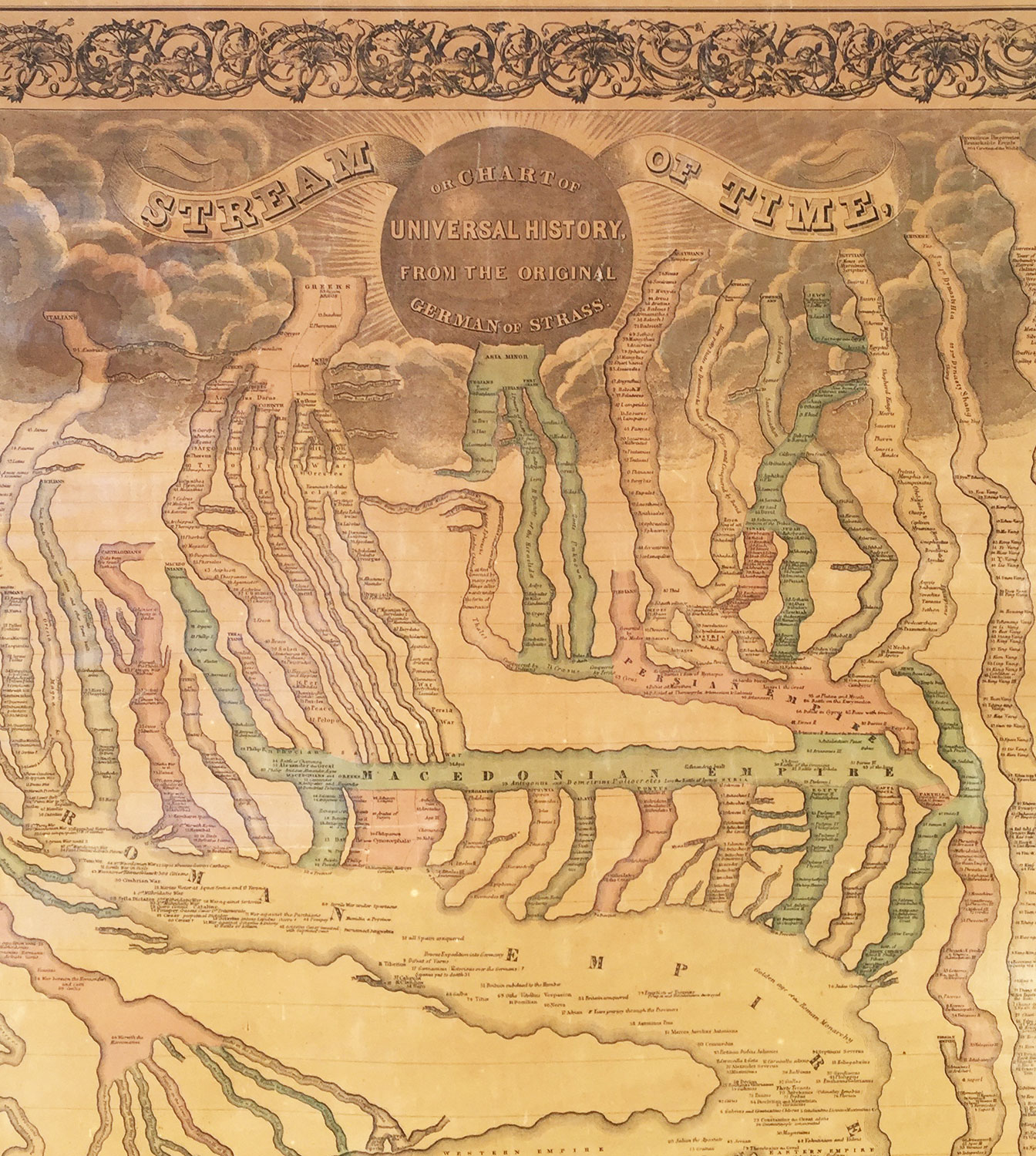

Image from Wikimedia commons.

2858 words.